Science and technological advances have always been a source of inspiration for artists. Among them is Martha Boto, a relevant figure in Kineticism, a movement that emerged in Paris in the late 1950s.

Born in Buenos Aires in 1925, Boto produced an exceptional body of work during the 1960s and 1970s by merging light, color, and movement in luminokinetic sculptures. These works were characterized by their refinement, sensuality, and great lyricism. The challenge in combining precision and scientific rigor with the poetic flow of an artist’s sensitivity was what critics praised a year after she settled in Paris in 1959.

Back then, Victor Vasarely, father of Op Art, produced works that generated virtual movement through different optical and chromatic effects. Vasarely had a significant influence on the kinetic artists, many of whom came from Latin America and starred at the forefront of Parisian art. Some artists formed artistic groups such as the Grav (Groupe de Recherche dArt Visuel). In contrast, others chose to work individually, as is the case of Martha Boto, her partner, Gregorio Vardánega, Alejandro Soto, or Carlos Cruz Diez, all essential references for young contemporary artists or neo-kineticists.

A matter that repeats in the History of Art is the low presence of female artists. And this Neo-avant-garde movement, from which very few artists emerged, is not exempt. Worth mentioning is Chilean artist Matilde Sánchez who was in Paris in the 60s producing kinetic work that focused on virtual movement. In the case of Martha Boto, there is an exceptional fact because both she and Gregorio Vardánega were pioneers in the use of the electric motor. Both made sculptures with real movement.

In 1960, a year after she arrived in the city of light, Martha Boto participated in the first Art Biennial in Paris. Soon, she was earning a place in the art world and was critically acclaimed. In 1961, she exhibited with Gregorio Vardánega in the Denise René gallery, a gallery where this art form emerged and where the most outstanding artists exhibited.

Currently, the work Martha Boto is being revalued and exhibited in several international museums. The Tate Modern has rescued her work from its private collection and revisited her talent in exhibitions, such as Shape of light: 100 years of photography and abstract art in 2018. In other museums, Kineticism seems to regain its vigor, as is the case of the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston that also has work by the artist. Now the MIA ART Collection, which owns Boto’s work, is opening an exhibition that contributes to explore better the artist’s work and her legacy.

Martha Boto’s kinetic work is widely recognized, but not the rest of her production. The artist continued creating in her studio located on the outskirts of Paris. She also continued exhibiting until her death in 2004.

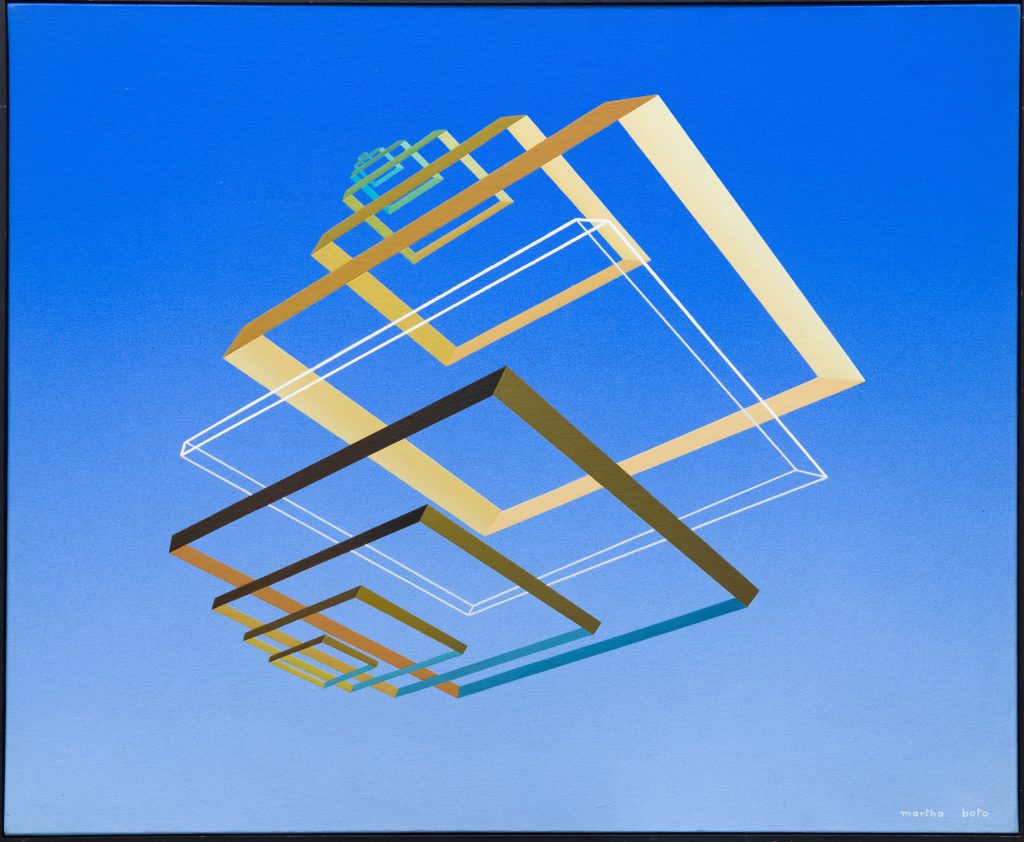

This exhibition offers an anthological overview of Boto’s work and emphasis her later creations done after her kinetic heyday of the 60s and 70s. Most of the pieces, paintings, and sculptures were produced between 1970 to 2000. This stage, associate to a lyrical and more playful kinetics, accounts for a multifaceted Martha Boto with a vast artistic repertoire. At the same time, certain aesthetic concerns and plastic elements remain present throughout her entire trajectory and production.

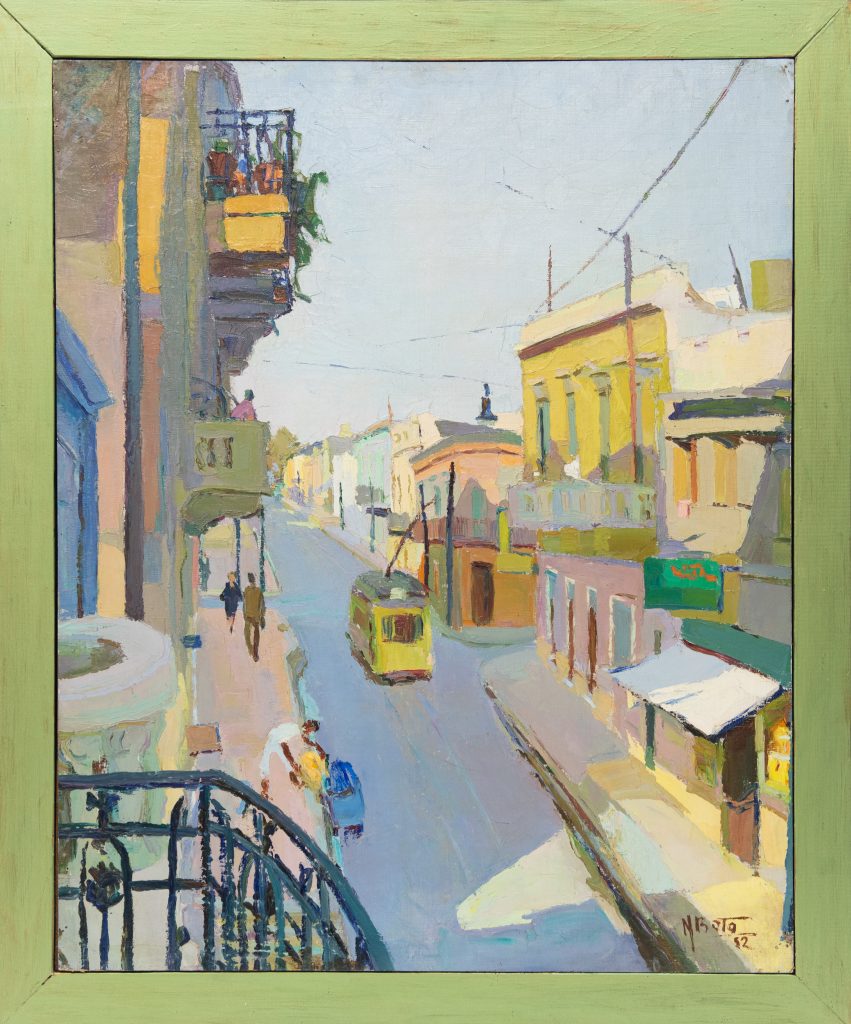

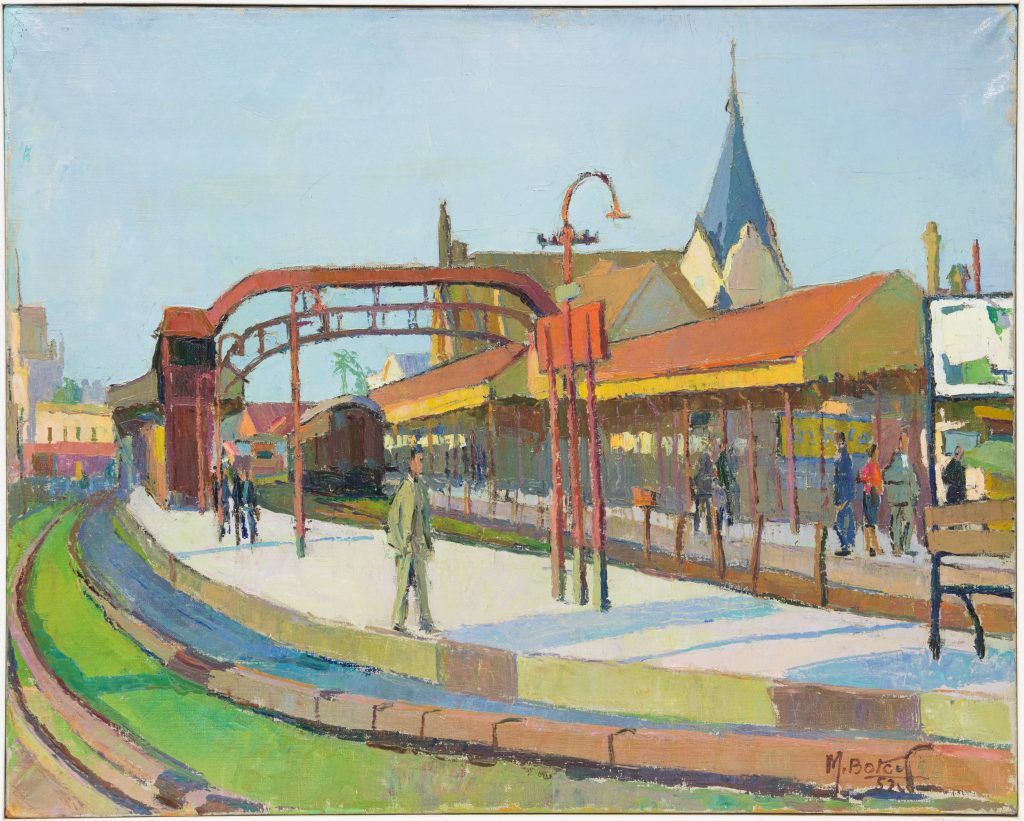

Back in the 50s, when she exhibited at the art galleries in Argentina, we can observe her first expressive explorations where she dealt with landscape and figuration. The years 54 and 55 will mark the way to a transition towards a lyrical abstraction evident in the play between background and figure, a certain organicity in the forms, as well as in the contrast of vast color planes that show her inclination for light and transparency.

In 1956 Martha Boto, together with her partner, Gregorio Vardánega, founded ANFA, non-figurative artists of Argentina. Three years later, the couple settled in Paris.

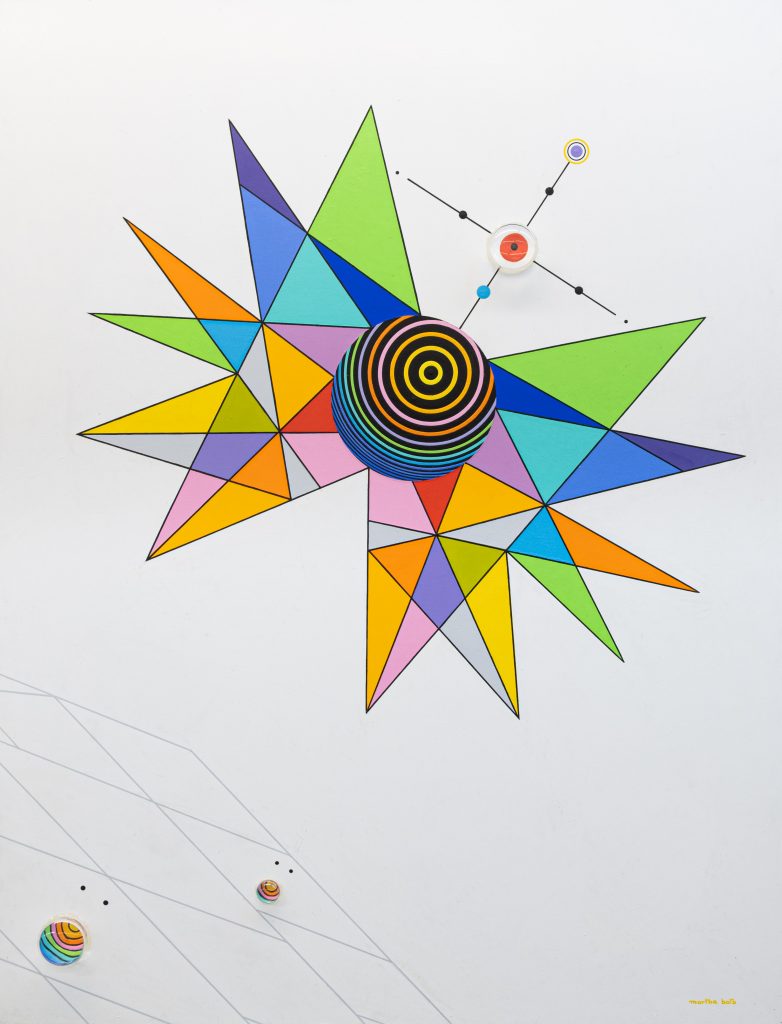

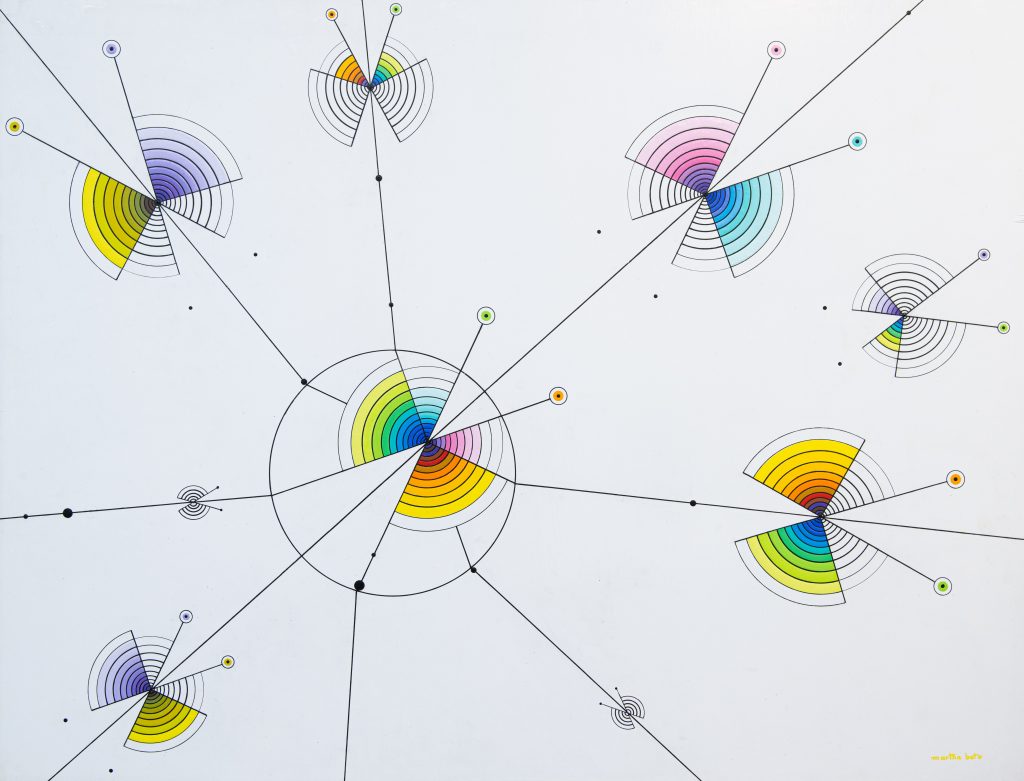

A constant in all her works is her interest in the secrets of the universe and the laws that govern it. Boto is passionate about the existence of its relationships and the mysterious system of balance. Her kinetic work, by analogy, is presented as a microcosm in continuous transformation. For this, she uses geometric forms as plexiglass discs or stainless-steel spheres that, when set in motion, refer to the planetary system.

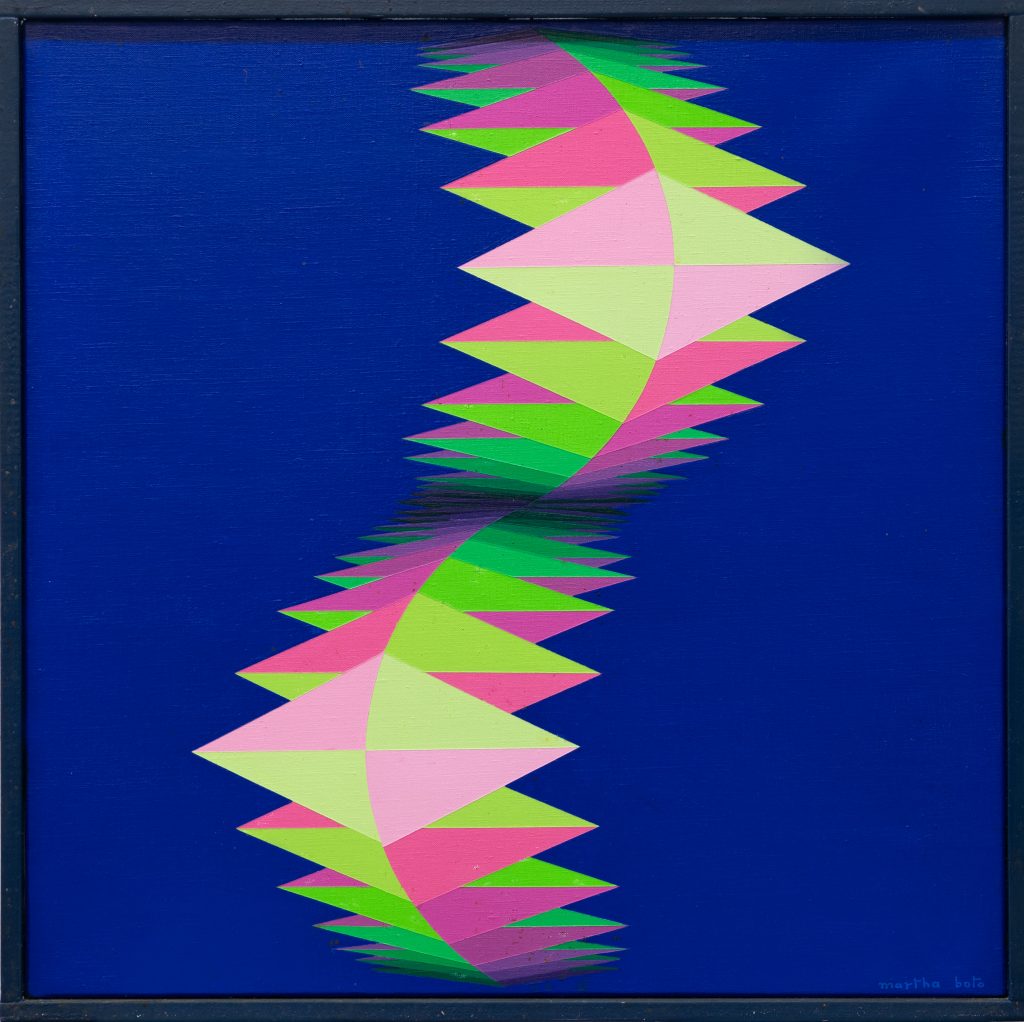

During the 70s and 80s, many of the titles of her paintings allude to the universe: Cosmos, Chromatic Eclipse, or Astral. We also observe how the same plastic vocabulary echoes throughout her geometric works. She makes use of simple figures, especially the circle and its derived forms, such as the ellipse or the helical shape.

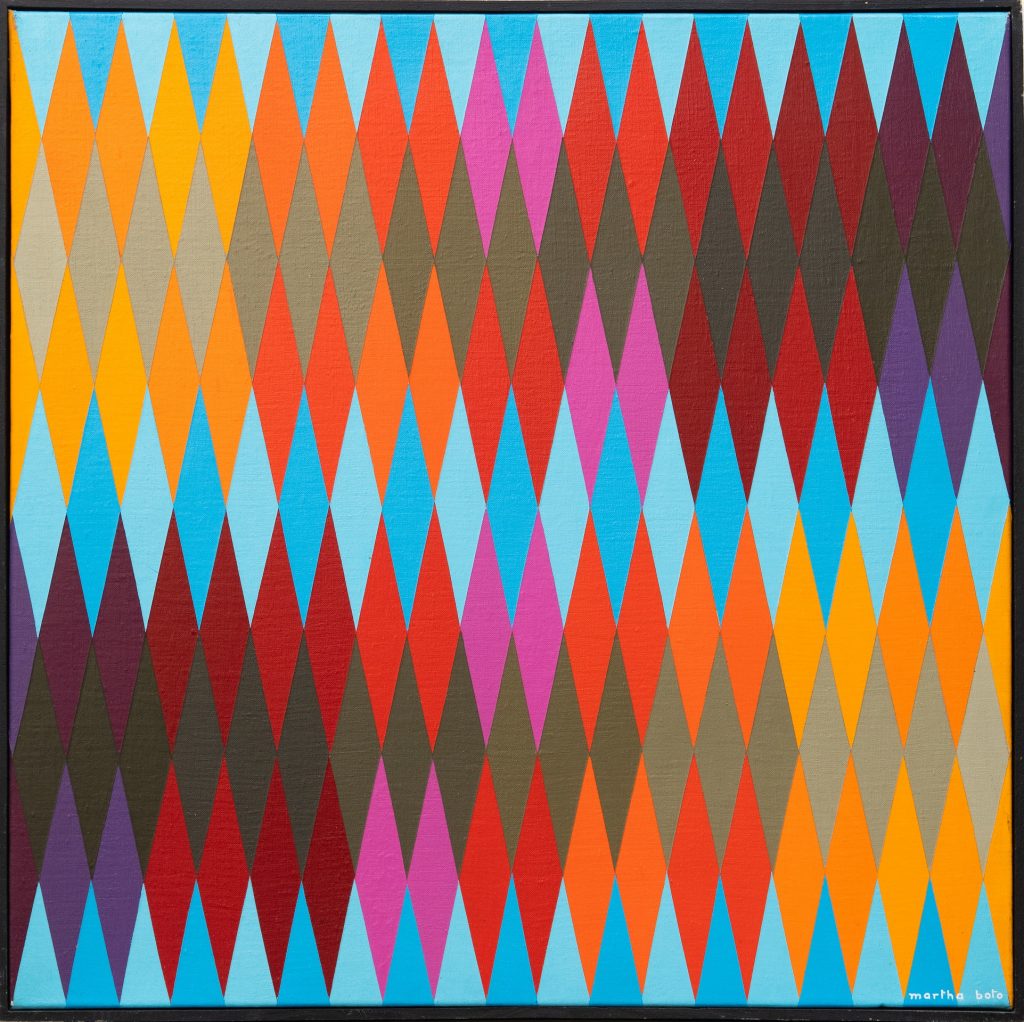

In these works, we observe the influence of Vasarely, where the use of optical effects provokes a sensation of movement. Her paintings from the 70s express chromatic vibrations produced by formal repetition, violent color contrasts, and use of transparencies that create ambiguity between background and figure. All of them are optical effects that produce visual instability and the feeling of movement.

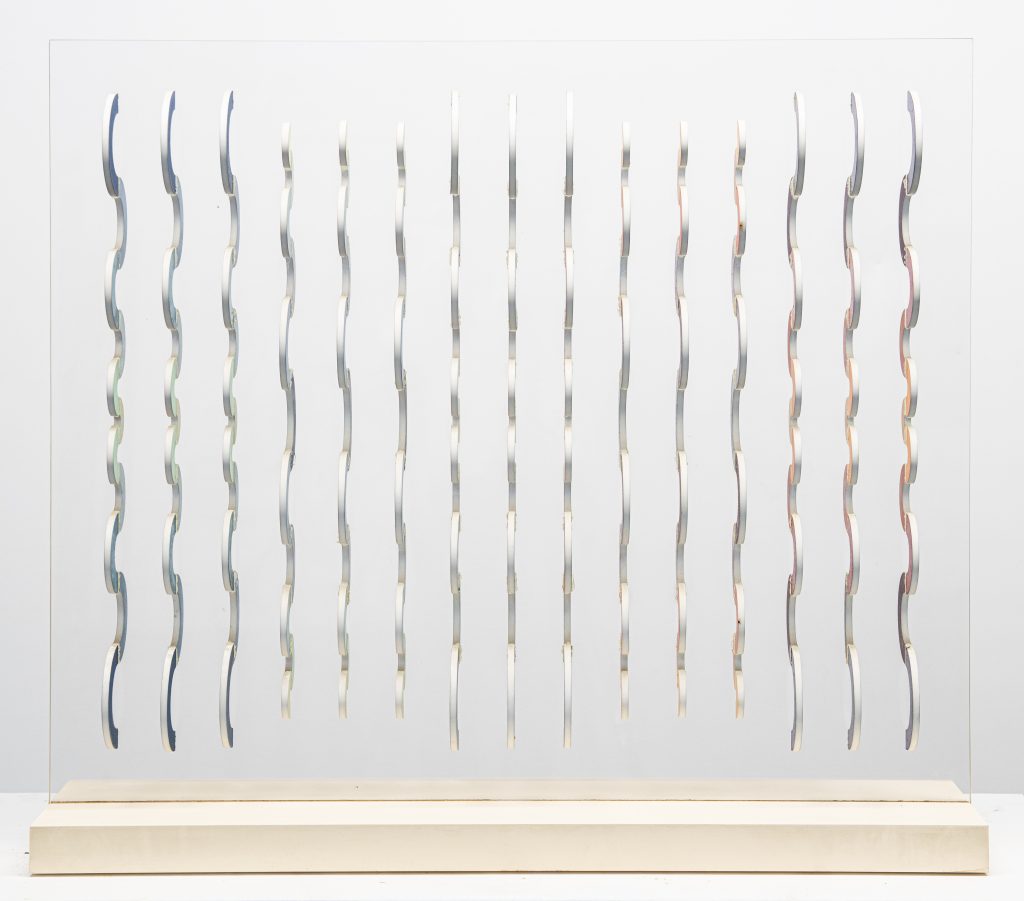

In her sculptures from the late 70s, engines do not intervene, there is no real movement in them. The dynamism and movement of these pieces come from the displacement of the viewer. The works transform according to the spectator’s point of view. Boto reintroduces Plexiglass in this works to produce invisibility and visual instability. Semicircles glued onto these transparent surfaces allows for a play with the color changes that occur with the human movement.

In other sculptures from the late 70s to the 80s, Boto makes use of painted wood with white acrylic to produce austere volumes that emphasize the purity of the meandering lines or their formal heaviness dominated by the curve and the hemisphere.

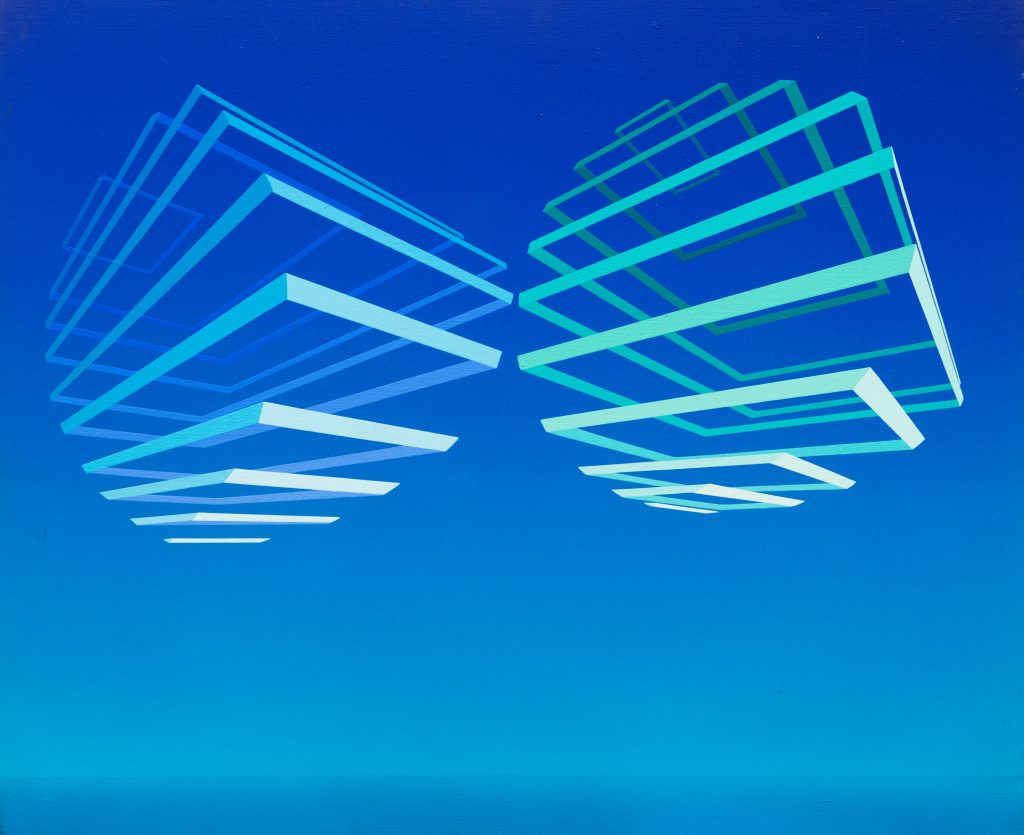

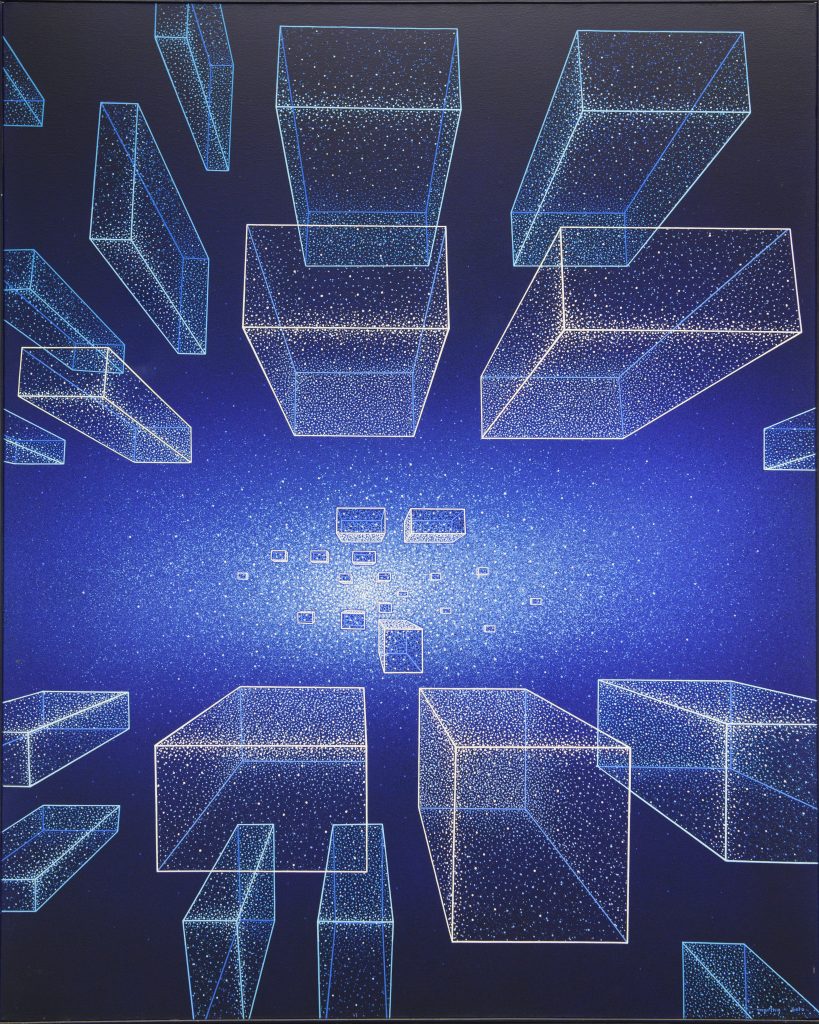

In 1981, Boto made a pictorial series that had a lunar atmosphere, where the figures floated weightlessly. In the treatment of the background, she kept her interest in light and transparencies. These are evident in the different tonal gradations of silent, cosmic blue. But this time, the protagonist is the space, carefully stressed by the play of light and perspective. Three-dimensional space occurs due to the effect of formal repetition and the different size gradients of the geometric figure.

In the following years, the artist continues to be imbued with the cosmic blue and the use of perspective. These paintings reveal the same formal concerns that animated her first electrical boxes in the 60s, where she studied the light diffractions, the progressive transformations of the images, their displacements, and their various light intensities. Now, in the pictorial space, movement slows down: shapes expand, project forward wanting to get out of the frame of reference.

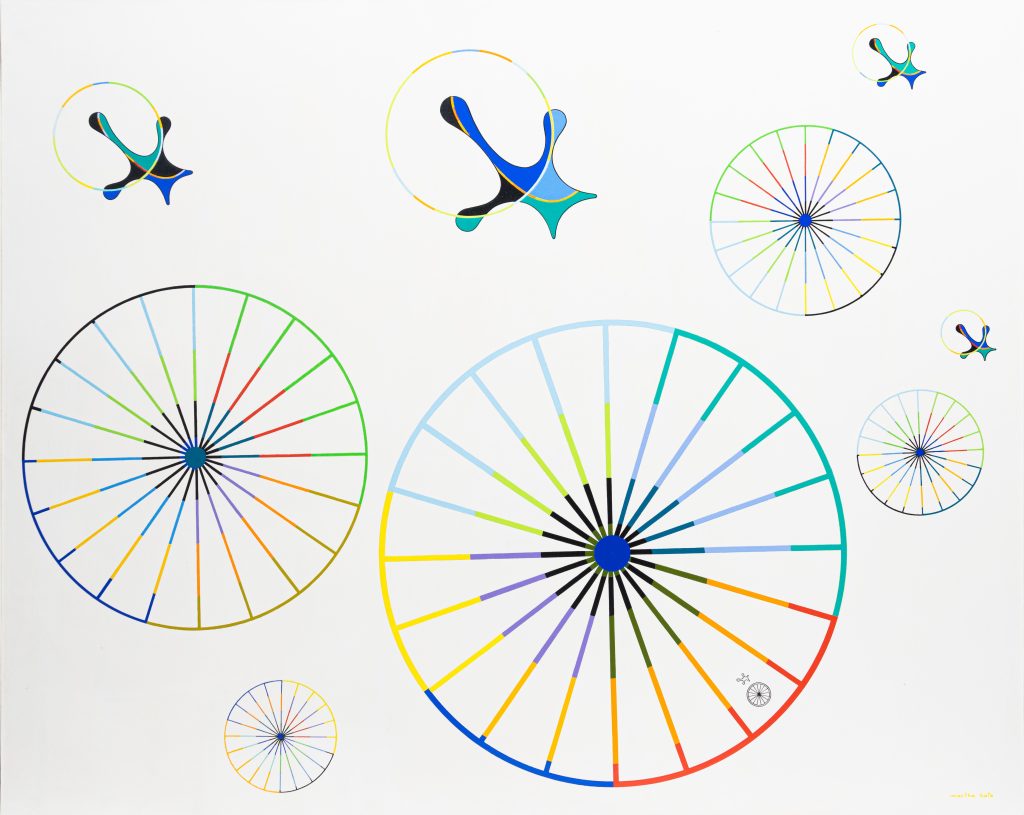

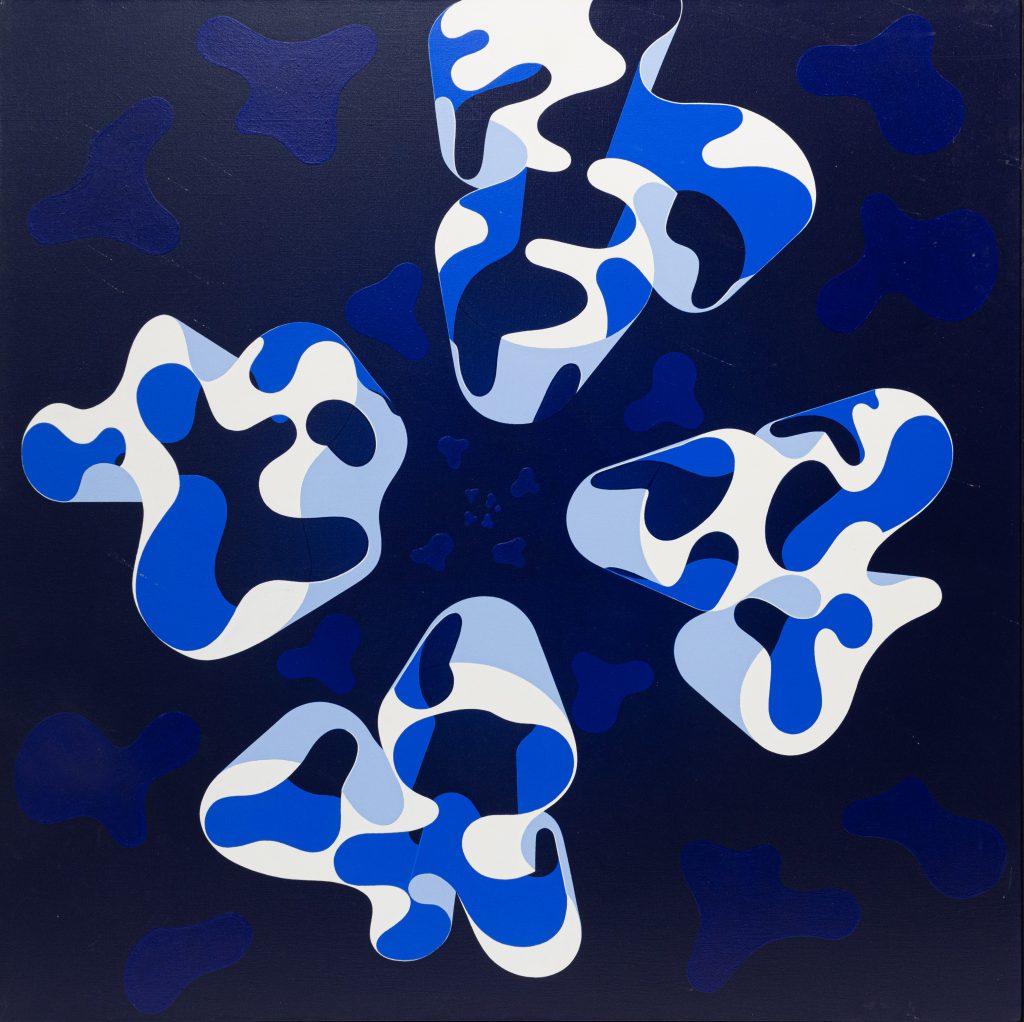

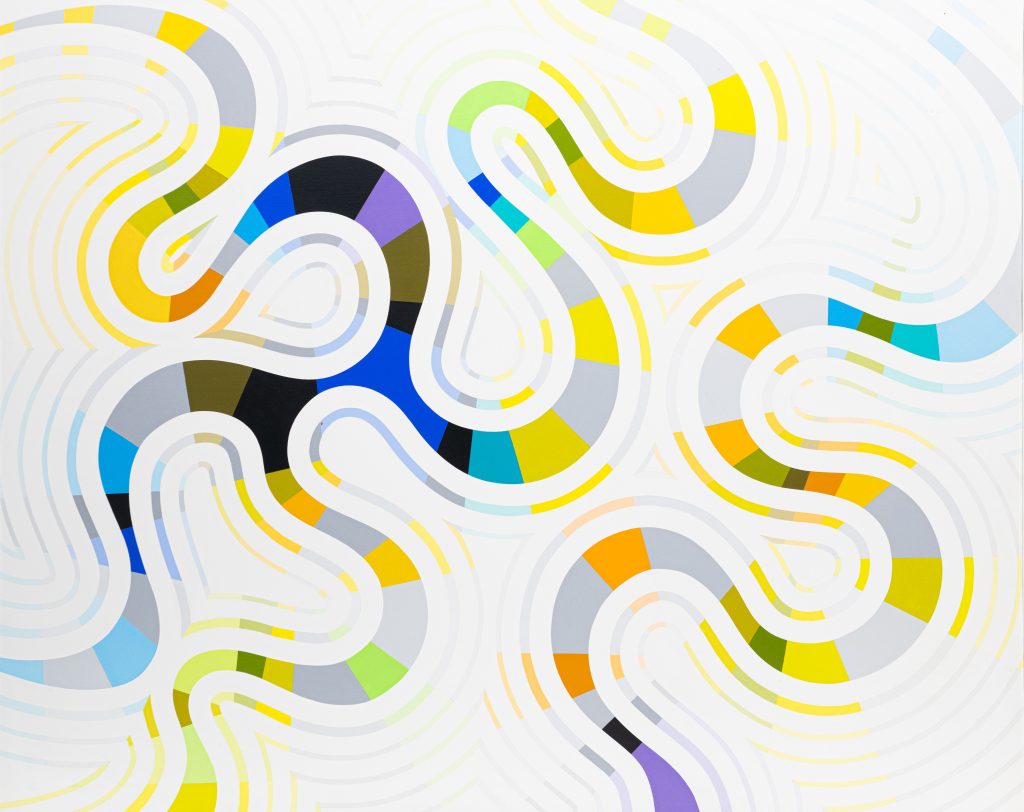

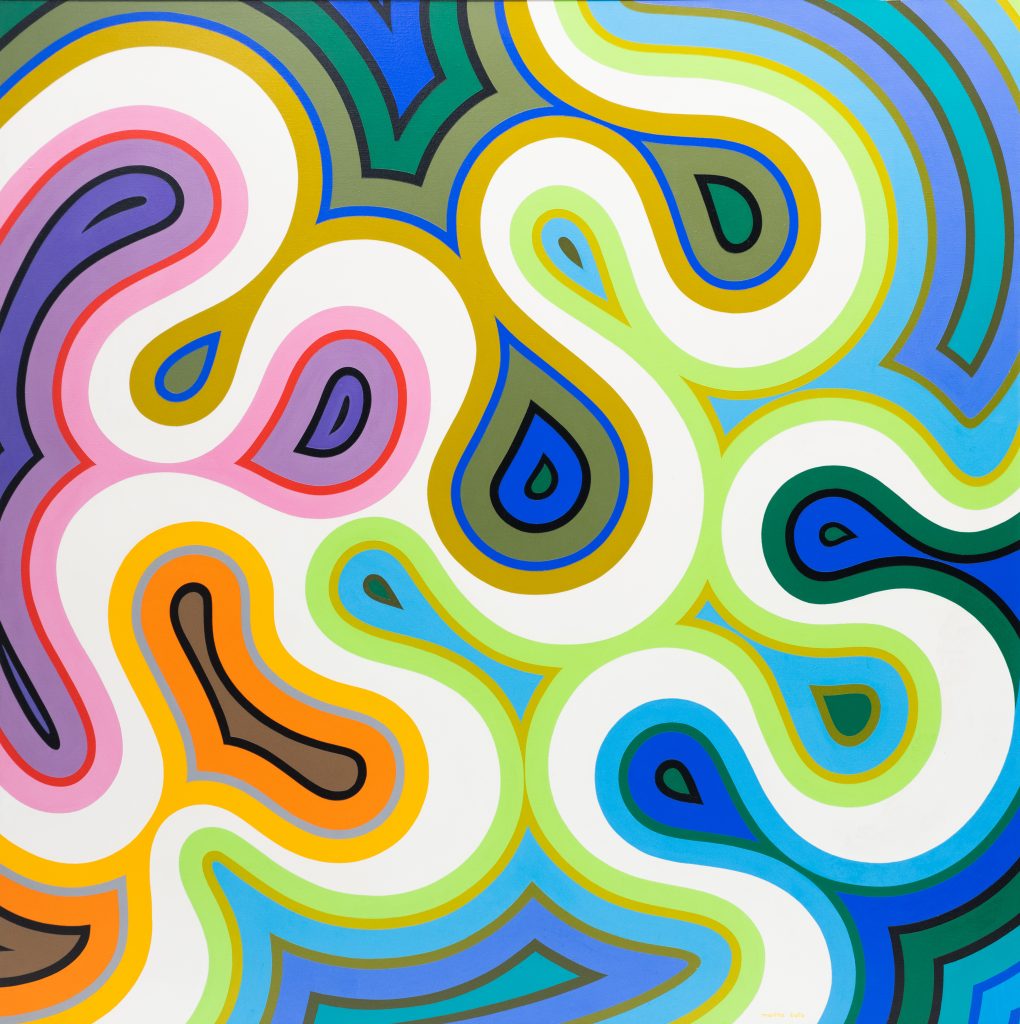

In the 90s, Boto changed her palette and allowed herself more formal freedom. The artist continued working with the notion of series, repetition, and its subtle variations—this plastic dynamism derived in meandering shapes where the curve dominated. The titles of her works allude to the organic and the vegetable kingdom. In some pieces, plexiglass relief reappears, mostly on monochrome backgrounds.

At the end of her career, around the year 2000, Boto performed a series of cyclists, she readopted the circular figure using the wheel. Color schemes and different size gradients gave dynamism to her compositions. The wheel personifies the continuous rotational movement of the universe as well as the cycle of life that persistently rotates to infinity.